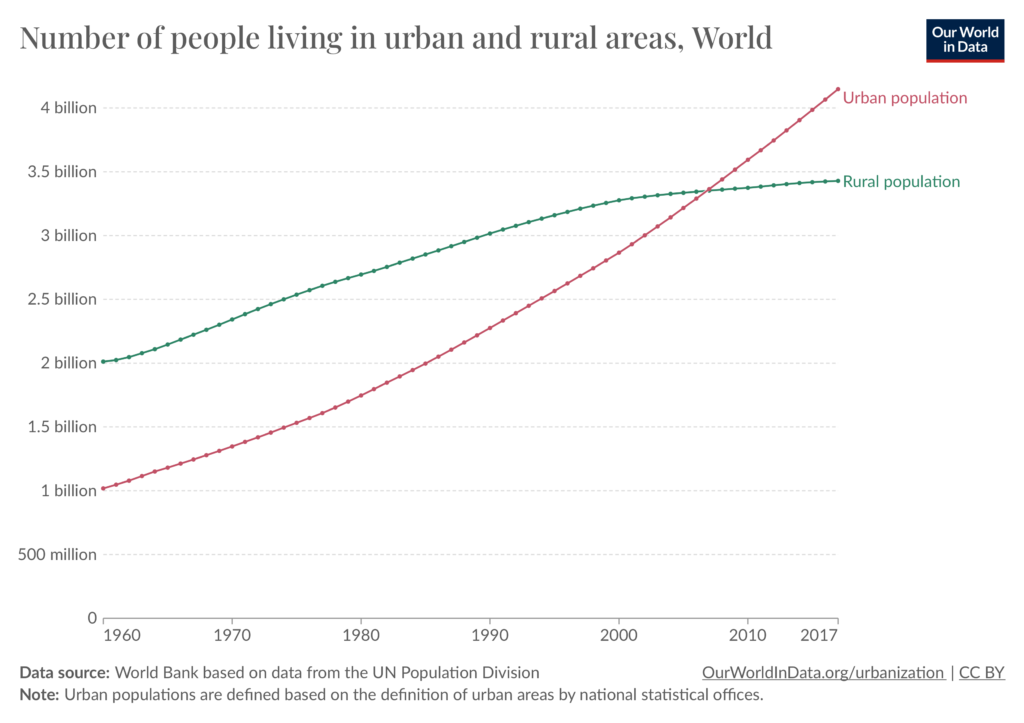

Almost every presentation I have seen in the last year started with the same graph showing how, in the future, the population will become increasingly urban in comparison to the rural population and how this justifies why we should research more on adapting dense cities which lack green spaces. But should we really talk just about dense cities?

You might tell me that this approach is to be expected in the field of urban green infrastructure studies and urban planning – of course, they both have „urban“ in their name! However, one does not need to be an urban planner to observe that we don’t all live in the same types of cities and that there is more to the dichotomy urban vs rural. I’m sure that you are like me and when you drive across your country you ponder on all those built-up areas composed of single family homes, shopping centers, car parks and DIY centers and wonder if that is a city, or just something in-between. The reality is that a large part of our urbanised spaces are neither rural nor dense urban centers.

In the field of climate adaptation, we have all heard of cities like Paris, New York and Singapoor which are heavily transforming themselves to integrate nature as a climate adaptation strategy. But how does this adaptation look like in these “in-between” cities, and should we focus more on these than on dense urban centers? Let’s look for some clues together!

Prelude – we must adapt our urban spaces

There is, of course, no doubt; cities are a central topic when it comes to climate adaptation. Indeed, on the one hand, they are the cause 70% of global CO2 emissions and other particles and on the other, they are very vulnerable locations because they concentrate large numbers of the population and will experience climate change effects in a multiplied manner. Cities are very often located in coastal areas and, therefore, are at great risk of sea level rise. Moreover, the heat island effect is predicted to cause the rise of temperature in cities to be twice as high as that of their rural surroundings. This is more and more recognised by the scientific community, and indeed this year, cities were given a seat at the discussion table in COP 28 as key players in local transformations.

But my interrogation comes from the fact that many research projects focused on urban adaptation, at least in the European context, are focused on the largest European cities. We have all heard of the climate adaptation strategies of Paris or Barcelona and, even though these projects are to be celebrated for their innovation and ambition, less attention is given to cities that are less iconic or on the urban periphery. Indeed, even for those large cities, the urban center, which attracts a lot of attention, is only a minimal part of the urban reality. For example, Barcelona city has approximately 1.6 million people within city limits, but including its periphery, it represents around 4.8 million people. This is why I would like to interrogate in this article: In what kind of cities do the 8 billion earthlings live?

Clue Nb.1 – Urban ≠ Urban

First, let’s have a look at what a city is. Well, actually, one important detail is that there is no universal definition of what is considered a city in a statistical way! The famous statistics from the UN estimates that 55% of the world population lives in cities relies on local definitions of cities from each country, and each country defines urban spaces very differently. Some countries use a minimum population threshold, while others rely on density or just have predefined city statuses for some urban areas.

Indeed, when Argentina defines urban areas as localities with 2000 inhabitants or more, Sweden defines them as built-up areas with 200 inhabitants or more and where houses are at most 200 meters apart, and Uruguay uses cities officially designed as such. This makes the comparison rather difficult. The website Our World in Data has collected all the data linked to the UN report very well and illustrates it with compelling diagrams, which we recommend you have a look at.

This inconsistency in definition doesn’t help us much more in understanding which type of cities those people live in. We must continue our search.

One interesting lead that could be helpful is the project Atlas of the human planet, which tried to systematically define urban areas to estimate urban population using its own definition and measuring it based on aerial images:

- Urban center: must have a minimum of 50,000 inhabitants plus a population density of at least 1500 people per square kilometre (km2) or density of build-up area greater than 50%.

- Urban cluster: must have a minimum of 5,000 inhabitants plus a population density of at least 300 people per square kilometre (km2).

- Rural: fewer than 5,000 inhabitants.

This definition led to an estimation of 52% of earthlings living in urban centers, 33% in urban clusters, and 15% in rural areas for the year of 2015. This sums up to a total of 85% of the world population – so much more than that estimated by the UN. Nonetheless, a revised edition of the UN document Our World’s Cities in 2018 also clarifies the difference between city proper, urban agglomeration and metropolitan areas.

Whether to know which definition is the most accurate is not the question-both can and are useful in their own way. However, this shows us that urban settlements can look very different, and when it comes to urban adaptation, we should be careful too not to assume cities all look the same.

source: ourworldindata.org

Clue Nb. 2 – In-between spaces

So, what does it imply that cities don’t all look the same? Based on what we said previously, i.e. that most research projects take place in large cities, this would lead us to think that all urban areas are very dense, are continuously built, have a mix of many functions and have a wide panel of infrastructure. However, when we look at another kind of urban space which we don’t directly consider “the city”, this vision is quite different. Here, I mean the in-between, the suburban, the diffuse city. These zones are where the city dissolves into a loose urban structure, where infrastructure is often limited to roads for cars, where open spaces are rather leftover spaces than planned green spaces, where one function prevails, often housing, and where there is no attractive center to be found.

Areal picture by night showing the continuous urban areas of the Padania region in Italy, the Ruhr region in Germany and the BeNeLux region. Image source: Nasa

Naming this mess

In Italy in 1990 and in Germany in 1996, this structure was starting to be named, La Città Diffusa (the diffuse city) and the Zwischenstadt (the in-between city). This latter concept, coined by Thomas Sieverts, a German planner, marked a turning point in German planning culture as it was the first time that this non-definable, non-characteristic, trivial urban structure was given a name, a definition and its own study. This period was a realisation for the German and European planners that everything that was built since the 70s was not following the model of the traditional “European city” anymore as described by T. Sieverts in an interview 25 years after the publication of his book; it had become an blend of built and unbuilt structures which has developed in an organic unplanned manner in response to vacant lots and low land value. This has led to fragmented urban spaces and a strong urban sprawl effect. In 2017, a study by Bremer S. estimated that in Germany, 75% of the German population lives in spaces of the Zwischenstadt.

This is, of course, not just a phenomenon in the European context. In the USA, the issue of urban sprawl and suburban areas has been well-known for many years and has fostered concerns in scientific and planning communities. In the South Asian context, the form of productive settlement halfway between urban and rural, called Desakota, is another illustration of this hybrid urban space, which does not look like a city as we might understand it in a traditional manner. Although these concepts of fragmented urban spaces have been thoroughly in the urban planning discourse, such in recent books like The Horizontal Metropolis by P. Vigano and C. Cavalieri, discussions in the field of nature-based solutions seem to still have to tackle this topic in more depth to identify what climate adaptation looks like in such areas.

Unplanned and vulnerable to climate change

Urban sprawl means that those settlements seal large amounts of natural land every year and develop, disregarding natural landscape logic. This is revealed to be critical for biodiversity habitat and can prove deadly in cases of extreme rain events. Through the years, some countries have implemented policies aimed at limiting those discontinuous structures. France has, for example, set itself the objective to achieve „zero net artificialisation of land“ by 2050. The counter effect of such policies ist that those urban structures are currently being strongly reidentified, and with the constant shift of population to urban areas as mentioned by the UN, this pressure on densification will be constantly rising. With accelerating climate change those zones will become more and more vulnerable and without larger urban strategies, their population is at great risk.

But these discontinuous urban structures can be a chance! Indeed, already in his book of 1996, Thomas Sieverts outlines the potential that this in-between city can represent in terms of landscape and natural elements. All those empty plots where nature has settled in could represent, in our time of nature-based climate adaptation, a great chance to achieve space for water retention, biodiversity habitat and fresh air corridors. This could be the hidden gem in urban areas and calls for further exploration!

Clue Nb. 3 – Nature-based adaptation of small and medium towns

“Large cities integrate adaptation to climate change by developing strategies, often supported by their own staff units and supported by (often local) science with vulnerability analyses. Small cities, especially those in peripheral locations, lack the corresponding capacities.” – Jakob K et al, 2022

Although less often mentioned, smaller municipalities have to come up with their very own solutions, which divert a lot from those of larger urban centres. These different conditions lead to challenges but also opportunities and experimentation. Stakeholders, spatial conditions, financial conditions, and uses are different and worth mentioning. We should of course celebrate larger cities that take ambitious measure of urban adaptation and set an example for the municipality which are willing to do the same but struggle to find the right support. However, when looking closer at examples in smaller municipalities, we can already see transformations happening! These differ from those in larger cities but are more adapted to these zones which are less dense and economically less advantaged.

A green oasis in a town center

The platform Opla is a good example for scanning through such inspiring examples. There we can find the example of the town of Ludwigsburg in the urban area of Stuttgart. An experimental green wall project was initiated by the regional organisation which searched for a location to implement it on the local scale. The case study reports that there were difficulties in finding an appropriate site and that the role of this larger regional institution was central to the success of this project. The resulting solution is a green wall in the center of this small town of 9000 inhabitants, which offers a cool island to the users of this space. This project was also a support for the larger climate adaptation plan of the town and sparked further similar initiatives in the town.

image source Helix Pflanzensysteme GmbH

A neighbourhood strategy for protection against heavy rain

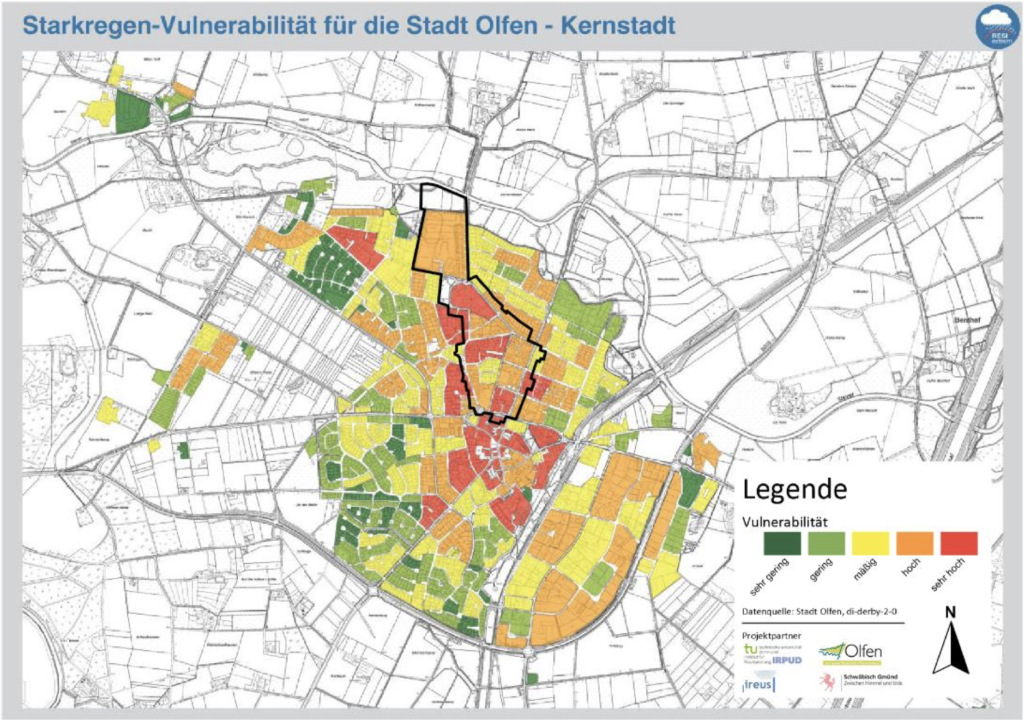

The living labs of Schwäbisch Gmünd (Baden-Württemberg) and Olfen (North Rhine-Westphalia) are examples of the benefits brought by the application of scientific modelling in the urban planning strategies of smaller municipalities. In this project, a new urban strategy was proposed to activate vacant lots and ensure more resilience in the case of extreme rain events in a discontinuous urban structure. This plan was then presented to the public to raise awareness of the need for large projects at a neighbourhood scale to ensure more cohesion and continuity of green and blue infrastructure. The scientists in charge of the report highlight the lack of expertise and financial capacities of small and middle-sized cities to implement ambitious resilience projects and emphasise that with the increasing densification of those towns, the vulnerability of such municipalities will be more and more critical without appropriate larger resiliency plans.

Extreme rain event vulnerability for the city Olfen. Image source: ISEK Stadt Olfen

To sum up

- The definition of “urban space” is strongly debated. Next time you hear that number, think about all the possible different types of urban spaces

- Suburban spaces are omnipresent! So, research should push them forward to the centre of attention!

- Developing strategies on a neighbourhood level in these fragmented spaces is the way to go to reach resilience!