Increasingly, we’re hearing about large-scale greenery in cities, but what does it take to create an urban forest? In this episode of the What’s That Green? podcast, we head to Georgia’s capital city, Tbilisi, to hear from Ben Hackenberger. From diseased pine monocultures to a forest shaped by community, ecology, and design, this episode explores what it really means to regrow green in a city.

Not all greenery is equal. Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, is often called a green city. Credit is due to past generations that have tried to keep nature in the city, but sometimes it needs a helping hand. In the 1960s, the Soviet administration planted monocultures of black pine across the hills above the city. These trees were fast-growing and efficient, but not diverse and, by the 2020s, were rapidly dying from pests and disease. Rather than let nature disappear, the city decided to act. That’s where Ruderal, a landscape architecture and planning studio based in Tbilisi, came in.

What is an Urban Forest?

All trees in a city are part of the urban forest. That includes historic woodlands that survived urbanisation, individual trees, those in private gardens, and any growing along roads and waterways, whether naturally or planted by human hand.

As with any greenery in the city, urban forests are important for the resilience of natural and city ecosystems, with a range of benefits: vegetation reduces the impact of extreme weather by withholding stormwater and cooling the air; they filter impurities, supporting better health; absorbing carbon dioxide, they’re a natural climate change mitigator; and they soften the aesthetics of the built environment, which improves the mood of people who live there.

Arguments in favour of urban greenery tend to lean toward the environmental and health benefits, but in Tbilisi, the look of the forest was a high priority.

Introducing Ruderal

That was done by Ruderal Landscape Architecture and Planning, and Ben Hackenberger, a landscape architect and researcher, explains how – over two separate projects – they made it diverse and visually pleasing.

Ruderal was founded in 2018 by Sarah Cowles and Ben joined a year later.

In botany, Ruderal is a word describing a plant species that grows on waste ground, the “ecological first responders” that restore life to spaces we may have assumed to be beyond hope.

Ben explains that they are species “adapted to disturbance”, a metaphor for how Ruderal the company works.

“All landscape architecture projects begin with an act of disturbance, especially in the context of construction projects: the site is usually ruined, it’s an ecological disaster.”

That perfectly describes the miscoloured back pine, showing signs of disease and death up on Mtatsminda, the mountain overlooking Tbilisi.

Ruderal’s role was to replant a forest there “as a starting point and set a new ecosystem in motion”.

Their work is grounded in this idea: not to erase the past, but to grow something new from it, ecologically, socially, and visually.

Ben explains that the architectural practice is ”thinking about how urban ecology can be worked with in a public-facing sense to make just places” and to imagine how urban ecosystems “can grow and expand and can bring beauty to urban landscapes”.

Focus on Ruderal Projects

Ruderal’s key urban forest interventions in Tbilisi include:

- Mtatsminda South Slope, above the Okrokana suburb

- Narikala Ridge, visible from Tbilisi’s historic centre.

Both sites were covered in failing black pine plantations. With support from the Development and Environment Fund, the city planned to restore these spaces into healthy, visually engaging forests.

Keeping the Community Happy

Because of the diseased trees – which was the majority by 2019 – the city had started to clear much of the forest. For a city with a reputation for being green, citizens did not respond well, but, Ben says, “it was absolutely necessary because they actually became a safety hazard” – dying trees can fall and injure people.

By replanting the forest, Ruderal wanted a variety of species that would provide “a safeguard against the uncertainties of the changing climate”. They were selected based on how well they could co-exist and for their visual palette, to provide a positive recreational experience.

Unlike in Soviet times, this was not a top-down approach. Tbilisi’s citizenry were consulted.

It was easy enough to arrange; the Development and Environment Fund runs tree planting events, so the ideas connecting urban forests and public good was long-running in the collective psyche. From these events, Ruderal was able to ascertain what people would like to see in their city.

As a result, they added colourful flowering plants to walking trails.

Designing a Living Forest

The Soviet administration planted the black pines to replace the forest that would have existed there up to 1,000 years ago. On the surface, it seems quite forward-thinking: directives from Moscow pushed state administrations to improve urban environments with initiatives like planting trees and “keeping certain areas of the city free of development to improve airflow”. But they had little clue about how to curate an ecologically rich ecosystem, a challenge the local administration also faced in 2021.

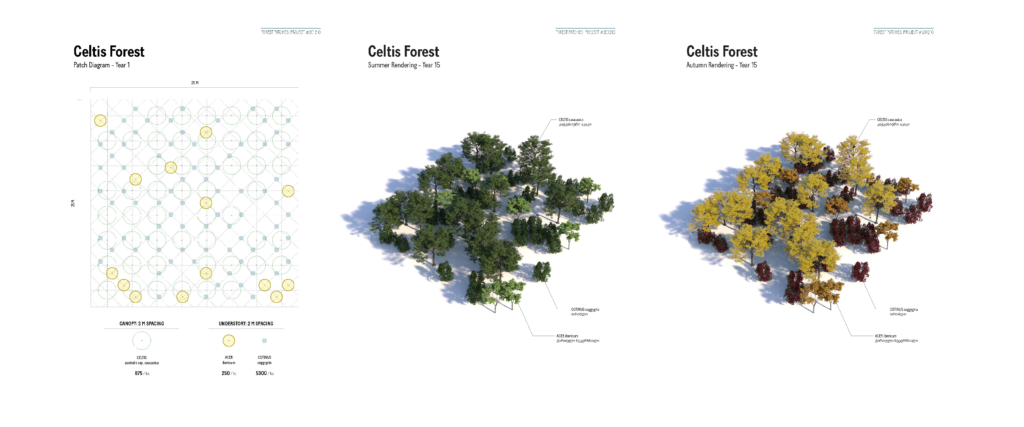

They did at least ask foresters, ecologists, and horticulturalists from the National Botanical Garden of Georgia for the “species that they thought would be most successful in diversifying the forest” and had identified six in all. But they laid out a plan on a spreadsheet, representing rows of tree species in straight lines, not knowing “how to mix them up in a way that will be aesthetically pleasing”. Ruderal’s involvement helped them to structure the planting.

For the second site, on Nardiala Ridge, Ruderal was invited to work with a couple of firms to enter the semi-public competition focused on developing the ridge above Tbilisi.

Most entrants proposed an icon or building “that could promote the ridge as a tourist destination”. The team including Ruderal instead looked into “how existing plant communities on that ridge can be amplified to make something visually interesting”.

Patch-based Design

Planting the forest was done by labourers, not horticulturalists. They were therefore not experts on the species in use, but were given specific instructions.

This “patch-based” design was inspired by landscape ecology, and Ruderal came to it by working with local experts and botanical scientists, which also allowed them to identify additional flora, expanding the species palette.

Ben says that each patch:

-

-

Hosts species adapted to specific sun, soil, and moisture conditions

-

-

-

Contributes to visually interesting seasonal displays

-

-

-

Encourages biodiversity and resilience through layered plant structures

-

To get to the design, Ruderal used digital tools.

Digital Tools

The team started by rendering concepts for the forest at the request of the client – the city. This is “normally a very intensive process for a design studio,” Ben admits, but they did it knowing how important the visual outcome was to people.

To simplify the process a little, the studio created a relational model through Grasshopper script, “a visual coding software that works in Rhinoceros, which is a digital modeling software”. This enabled them to take scientific data and translate the possibilities into easy to understand visuals. “They were highly specific to context because it was the exact number of trees that we would use, it was the exact type of species.”

The problem was that they hadn’t yet seen the species in person.

Although the model used a “specific Georgian version of the plants”, in the nursery they looked (and behaved) differently, so Ruderal had to alter the model. “It was a little bit of data overload and overwhelming at times” but the renderings did inform decisions about layout based on how different species grow and their needs for soil depth, water, light, and space.

To dive deeper into the Mtatsminda and Narikala projects, and Ruderal’s full methodology, check out: Ruderal Substack & Visual essay in SPOOL Journal

Host and co-writer: Fanny Téoule

Guest: Ben Hackenberger

Audio editor and writer: Karl Dickinson

Music composer: Jenny Nedosekina

Graphic designer: Vivian Monteiro, Swanandee Nulkar & Julia Micklewright